- Home

- Lynn Bushell

Painted Ladies Page 2

Painted Ladies Read online

Page 2

‘Aren’t you feeling chilly in that coat?’ Those were the first words Marguerite had ever said to her.

‘I grew up in a house in Bobigny that only had a fireplace in the kitchen. I don’t feel the cold.’

‘You travel in each day from Bobigny?’

‘No. I’ve got lodgings in the 10th.’

‘I work as a stenographer,’ said Marguerite. ‘I get off at the Mairie in Saint-Martin.’ Had Renée been in any doubt, she now knew Marguerite was in a class above her. ‘I allow myself an hour for the journey. You can never count on getting there in time.’

‘I’m always late,’ said Renée and then thought, why did I say that?

Marguerite gave her a condescending little smile. She sometimes read Le Figaro while she was on the bus. ‘The war is going badly,’ she said one day as she scanned the columns and then in a voice so low that she might have been talking to herself, she added, ‘Do you ever wonder what it would be like to not exist?’

‘Do you mean to be dead?’ said Renée. She’d occasionally thought about it when there was an air raid and she hadn’t managed to get down into the cellar. Once there had been a direct hit on the tenement next door and a woman she had often spoken to when they met in the market had been killed along with two of her small children. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I think about it all the time.’ That was the moment, she thinks now, when Marguerite’s attention focused on her properly.

‘The girl I share with will be moving out next month,’ said Marguerite, one evening when they met up on the homeward journey. ‘You could come and have a look at my apartment as you’re here?’

Is she inviting me to share it with her? Renée wondered. So far, nothing they had said, apart from the discussion about being dead, had told them anything about each other. They got off together at the next stop, nonetheless, and walked the two blocks through the narrow streets to Belleville. It was not an area that had pretensions to gentility, especially since the outbreak of the war. The Zeppelins had targeted the 18th and the 20th arrondissements relentlessly. They walked through streets in which the only things left standing were the iron bases of the street lamps. Renée peered in through the shattered door of a brocante. Boys of six and seven scooted in and out among the debris carrying whatever loot they could lay hands on. In the rue de Borrego, the end wall of a tenement had been shorn off and in a first-floor bedroom Renée saw a black cat curled up on a brass bed with its sagging mattress still in place and, underneath, a chamber pot that had been shielded from the blast.

‘That raid was mentioned in Le Figaro,’ said Marguerite. ‘The Zeppelins dropped nineteen bombs that night. They had a special funeral at Notre Dame La Croix for those who died.’ She turned into an alleyway. The gunnels ran with water. Renée’s shoes squelched as she followed her. They crossed a courtyard where smashed window boxes and the dead geraniums they had contained were piled haphazardly next to the rubbish bins.

‘It’s on the third floor,’ Marguerite strode up the stairs ahead of her. Her footsteps echoed on the concrete tiles. The stairwell smelt of dust and cabbage. The two rooms inside the flat were similarly uninviting. There was very little furniture and nothing on the walls except a reproduction of the Pont Neuf and a print of Paris from Les Invalides. The only items that suggested comfort were a sofa with two cushions on it and a rag rug on the bedroom floor.

‘It’s very nice,’ said Renée.

‘What are you paying for the place you’ve got at present?’

Renée told her, and she did the calculations. ‘All right, you can pay that here. It means I’m paying more but you can make it up in other ways.’

And that was how it happened. Three months later she was sharing Marguerite’s apartment and discovering the ways in which she was expected to make up the shortfall in the rent. Although the flat had only one bed, Marguerite had not suggested that they get another. Renée wondered if the previous girl had taken her bed with her when she left. She had been used to sharing with her sisters, so it didn’t feel unnatural to do that here. On Sundays, if they woke up early, she and Marguerite lay listening to the street sounds down below. ‘I’m going to pretend that you’re a little pat of butter,’ Marguerite would whisper. ‘I shall hold you so tight that you melt.’ They giggled like two schoolgirls.

She occasionally fell asleep with Marguerite’s hand on her stomach or her thigh and sometimes found her body answering the pressure of the fingers. She had grown accustomed in the past to pleasuring herself although she knew it was a sin. When Renée had to choose between a pleasure and adherence to a code of practice that forbade it, usually the pleasure won out.

One night after Marguerite had gone to sleep with her hand curled round Renée’s thigh, the fingers quivering involuntarily, she had an urge to move her body just a fraction to engage with them. She lay there in an agony of longing until almost imperceptibly she felt the fingers relocating to the cleft between her legs that, in that instant, seemed to harbour every impulse and sensation she had ever felt.

As Renée’s moans became more audible, there was no other sign from Marguerite that she had woken up except a whispered, ‘There, there,’ like an adult calming down a child it has provoked. As she lay, her hair plastered to her forehead, her heart banging so hard on her ribcage that she was afraid it might burst through, her gratitude was tempered by the knowledge that from now on Marguerite would have complete control over her life. Her small acts of rebellion were her only means of clinging to some last shred of autonomy. She sometimes felt that she was passing straight from childhood into middle age and that her one experience of what romantic love might be like was that night when Marguerite had first made love to her. But even then, it seemed like something she’d experienced, not something they’d experienced together.

‘Is that where I’m meant to take my clothes off?’ Renée pulls the curtain back. There is a ledge inside the cubicle and, hanging on a hook, a dressing gown. The room reminds her of the nests mice make, stuffed full of chewed-up rags and scraps of paper. There is nothing in it other than a chaise longue and a table with a palette and a jar of brushes – some round, some like chisels, some with handles so long that they look like brooms. The smell is cloying. Renée’s brother, Tonio, has that scent on him when he comes back from the factory, but this smell is sweeter. It’s the combination of the linseed with the vase of asters on the windowsill.

Next to a poster with a painting of a garden and ‘Les Nabis’ scrawled across the front in purple paint, a canvas has been tacked onto the wall. A light breeze catches underneath the fraying edges and the heavy linen lifts and sighs. She touches it. The paint is still wet and it comes off on her finger.

She looks back over her shoulder to see whether he has noticed. He picks out a paint rag from the pile next to the door and hands it to her. There’s a blue smear on her finger after she has rubbed the paint off. She hands back the rag. He’s not as friendly as he was when he was talking to her in the store. She wishes that she hadn’t come. Her eyes move round the room like agitated butterflies, returning to the cubicle. The dressing gown is silk. It has a faint scent. Someone else has worn it.

‘Who was here before me?’

‘I’ve had several models. No one in particular.’

‘What happened to them?’

‘Some of them went on to sit for other painters. Some of them got married or found other jobs.’

‘It isn’t permanent then?’

‘That depends.’

‘There’s no point in me giving up my Wednesdays if in three months’ time you suddenly decide you’ve finished with me.’ She sounds brittle. Who said anything about it being permanent? She came here thinking she would probably decide against it anyway. Now suddenly she’s acting like she thought she’d get a pension when she leaves. She thinks she’ll hit him if he smiles at her like that again. She keeps on saying things that make her sound naive or grasping. It’s because he says so little that she’s babbling.

The

re is something on the table that is helping to persuade her. It’s a cake – a mille-feuille with cream oozing out the sides. The cream’s not real, of course. The pastry won’t be, either. Bread’s been rationed for the past year. You can’t even buy a brioche in the bakery. He sees her looking at it. On a Sunday, Mother usually does a suet pudding sweetened with molasses, but she can still feel the weight of that the next day. This looks so light it’ll float into her mouth. She shrugs as if she doesn’t care if there’s a cake or not, but he knows that she does.

Outside it has begun to rain. The wind is blowing leaves onto the skylight. It feels warm inside. She notices the stove is lit. Unless she takes her coat off while she’s in here, she’ll feel chilly when she leaves. She slides it off her shoulders. ‘What’s the deal, then?’ she says, airily.

I knew, of course. I knew the minute that it started. Women do. It’s not as if she was the first. The others didn’t matter. There were some among our so-called friends who changed their mistresses more often than they changed their shirts. He wasn’t like that. Sex for Pierre was never an obsession. It was something to be got out of the way so he could concentrate on work. I wasn’t just the woman in his life. I was the muse. Without me, there would be no pictures. You can’t wipe out quarter of a century.

I didn’t care much for his painting to begin with, though I never said so. It was hardly my place to start criticising him before I’d even got my foot inside the door. I’d look at what he’d done and think, ‘It’s not bad and I like the colour, but he hasn’t drawn the table properly. It looks as if it’s been tipped up.’ You’d see a plate that looked real, but there’d be an orange on it that was floating in the air. I thought, ‘Well, after all, he hasn’t been an artist very long. He’ll probably get better.’ I was wondering how I could fit into the space between the window and the door without the table cutting me in half.

‘It’s not important, Marthe,’ Pierre said. Not to him, I dare say.

He was renting a small studio in rue de Douai with an alcove for a bedroom and a kitchen with a tin bath hanging on the wall. Not that I’d come from anything much better. I had seven brothers and my father was a navvy on the railways. I suppose my mother must have loved him, but in our class no one talked of love much. On a weekday he came home each evening, ate and went to bed. At weekends he got drunk and beat her. What’s to love?

Pierre would have been riveted by Mother’s bruises on a Sunday morning and the way they changed from blue to bluish-purple, then to yellow and eventually to black. It wouldn’t have occurred to him to ask her where they came from, any more than it occurred to him to ask me where I’d got a yellow headscarf or a vase. The only thing Pierre insisted on was that whatever came into our living space remained there.

If we’d had a child, that might have changed us. Children break things. They wear out the rugs. They eat the still lifes. Children were another subject that we didn’t talk about. I lost one, three years after we moved in together, when my mother wrote to tell me that my father had been killed by falling masonry. I knew the baby was a girl. I called her Suzanne. On the day she died, a cat came scratching at the door. I should have turned her out, but I was needy, so I poured a saucerful of milk and let her drink.

If we had had a baby, I suppose he would have put that in the paintings, too: a white blob in what could have been a coffin or a crib. I sometimes wondered if the bathtub hadn’t turned into a tomb, as well – a tin sarcophagus.

He’s left three francs inside the cubicle. Is this so that he doesn’t have to hand the money over to her? Renée hears him humming as he moves around the studio, the clink of glass, the glug of liquid being poured into a jar, the rustling of paper. She reminds herself she’s not the first girl who has been here. She remembers that faint whiff of scent inside the cubicle the first time she pulled back the curtain. It’s not there now. Either she’s accustomed to it or already her scent has replaced it.

She can’t stay in here for ever. She wraps the kimono round her, so that there’s a double layer at the front, and clasps it to her stomach. Swishing back the curtain, she steps out onto the rug. There is a tin bath in the corner, underneath the skylight. When she came the first time, it was propped against the wall. He sees her looking at it. She’s still clutching her kimono. ‘What do you want me to do, then?’

‘If you could take a position near the bath, as if you’ve just got out of it, perhaps, with one hand on the rim . . .’

She fumbles with the wrap. It’s getting in the way but she can’t bring herself to take it off yet. She goes over to the bath and bends down. ‘Like that?’

‘Yes, but I can’t see your body while you’ve got the wrap on.’

It’s all right for you, she thinks. She wonders how he’d feel if he was standing there with next to nothing on while someone stared at him. This isn’t working out the way she had expected. She thought he’d be grateful that she’d bothered to turn up, concerned to put her at her ease. Instead, he grunts, makes huffing noises, mutters to himself as if she wasn’t there and shunts her back and forwards like a piece of furniture. There is a moment when she thinks she’ll straighten up, march back into the cubicle, get dressed again and leave.

‘The wrap,’ he prompts.

She hesitates. How does she get herself into these situations? Suddenly a beam of sunlight filters through the cracked glass of the skylight and illuminates her arm and the exposed part of her thigh. She sees the shadow cast across her foot by one side of the tin bath and the ripple of the light across the floorboards. She throws off the wrap. Her costume is her skin. She is no longer Renée Montchaty, a shop assistant on a perfume counter. She is Aphrodite, Liberty, the Sibyl.

‘Yes,’ he murmurs. ‘Yes, that’s very nice.’

Madame Hébert came by this morning. I would rather not have had a local woman in to do for us – I hate these Norman peasants with their mean eyes and their thin lips. ‘No doubt you’ve been busy,’ she says, knowing that my only task in life when Pierre is here is to have baths or sit around and wait for him to get the sketchbook out. The walls are choc-a-bloc with pictures and they all have me there, doing more or less what I am doing now – not much, in other words. She crops up in a couple of them too, though fortunately when she does she’s on her feet and has at least got something in her hands. It wouldn’t do for Pierre to imply that she’s as lazy as his wife. They call me ‘Madame’ in the neighbourhood, but they know Pierre and I aren’t married. That’s the first thing they’ll have sussed out.

When my mother was in service, she said that the women from the upper classes were all slatterns when it came to housework. That’s why they got someone else to do it for them. I knew if I showed an interest, it would be a giveaway.

Pierre didn’t see the dust as dust, in any case. Sometimes I’d sit there in the spot where he’d been sitting and I’d try to see what he saw. Once when he had left his glasses looped over a chair, I put them on. It made the particles of dust look bigger, but they were the sort of brownish-grey you see on uncooked chicken. Then the sun came out and all at once I saw what he saw – only for a second and never again – but I at least knew it was there. He wasn’t seeing things. No, my Pierre was seeing things.

Madame Hébert and I sit down and have a chat before she starts to clean. She’s always called me ‘Marthe’ whereas I’ve no option but to go on calling her ‘Madame’ because she hasn’t told me what her Christian name is. It’s deliberate. She knows we’re equal and that means we can’t be friends. Pierre must be the only person who accepts the lie. Perhaps there are so many lies between us that one more is neither here nor there. And he could hardly say at the beginning, ‘Your name is de Méligny?’ and give me one of those slow smiles of his and then add, ‘I don’t think so.’ ‘Marthe’ is the compromise we both accept. At least I feel at home with it.

She’s stopped undressing in the cubicle because the sight of her unravelling a stocking or unbuttoning her blouse will frequently turn out to b

e the pose he needs. Sometimes, when she is taking off her clothes in front of him, she knows he’s watching her and that the look is not the same as when she’s posing for him. She may not know what the difference is, but she knows that there is one.

When he’s painting her, he seems so totally absorbed in what he’s doing, it’s as if she isn’t there at all. Sometimes she speaks to him and there’s no answer, or he looks up, startled, as if he’s not certain where the voice is coming from. ‘I’m sorry,’ he says. ‘Did you speak?’

She sometimes gets a glimpse of what he’s working on, but usually when they stop he throws a sheet across the easel. Once, while he is busy at the sink, she lifts a corner of the sheet. She turns and sees him glance at her. ‘Am I allowed to look?’

‘I would prefer it if you didn’t.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t want to be influenced by your reaction.’

She is flattered that he could be influenced by anything she said or did. ‘I wouldn’t tell you if I didn’t like it.’

‘That’s not what I meant. I meant your attitude towards yourself might influence my attitude towards you.’

It’s a bit too deep for her. ‘But if I told you which bits didn’t look like me, you’d know what needed changing.’

‘Do you think you see yourself that clearly?’

‘I know what I look like.’

‘Yes, of course you do.’ He smiles as if he knows something she doesn’t. ‘You can see it when it’s finished.’

He puts out two cups. He only has two. They’re a cheap white china and they’re both cracked. One leaks but so slowly that she doesn’t think he’s noticed. He sits opposite her on the chaise longue with his knees together and the cup and saucer balanced in his lap. He’s not worn anything except the black suit all the time she’s known him. Often he paints with his jacket on and there are blue stains down the front of it. It’s odd that when he does spill paint it’s always blue. He wears a white shirt buttoned at the neck. She’s noticed that the cuffs and collars have been turned on all of them. She wonders whether Marthe does this out of habit since they can’t be so poor that she does it from necessity.

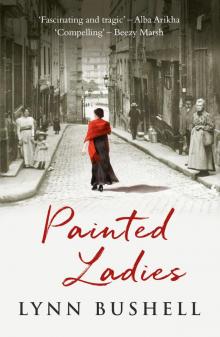

Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies