- Home

- Lynn Bushell

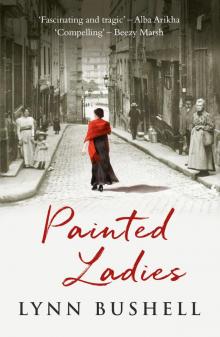

Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Read online

Lynn Bushell has drawn on her own career as a painter and art historian to explore the relationship between the artist Pierre Bonnard and the rival women in his life. She has won prizes for her short stories and her articles have appeared in Art Review, the Guardian and the Observer. She is married to architect Jeremy Eldridge and divides her time between a house on the Suffolk borders and a working retreat on the Normandy coast.

Also by Lynn Bushell

Remember Me

Schopenhauer’s Porcupines

First published in Great Britain by

Sandstone Press Ltd

Dochcarty Road

Dingwall

Ross-shire

IV15 9UG

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored or transmitted in any form without the express

written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Lynn Bushell 2018

Editor: Alison Lang

The moral right of Lynn Bushell to be recognised as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Creative Scotland

towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-912240-48-7

ISBNe: 978-1-912240-49-4

Cover design by Rose Cooper

Ebook compilation by Iolaire Typography, Newtonmore

For

Pippa

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

1917

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PROLOGUE

Paris 1893

I sometimes wonder if our whole life isn’t just a random accident. Ten seconds either way and we’d have missed each other. There I was, stuck in the middle of the rue du Bac, a costermonger’s cart on one side and a carriage on the other, neither of the bastards willing to give way, steam coming from the horses’ nostrils and sparks flying from the cobbles. And then there’s the rain – the sort you only get in Paris. It’s a mean rain, sleety, with a chill that gets you right through to the bone.

He’s watching from the pavement opposite as if all this is a performance that I’m putting on to liven up the morning. He could be a toff or somebody who only has one coat and sleeps in it – it’s hard to tell. He’s dressed in black from head to foot. I can remember thinking, ‘If I fall under the wheels of one of these carts, this is who’ll be there to greet me on the other side. That, or he’ll be the undertaker.’

There’s a moment when the street and everybody on it seems to hold its breath. And then he steps into the road and takes my arm. Up close he’s scruffy, but there’s an expensive smell about him, as if he has washed first before putting on old clothes. He asks me where I’m going and I say, ‘The dead house.’ He’s not sure he’s heard me right. ‘I work there,’ I say. ‘I sew flowers on the wreaths.’

‘You don’t regret it, Marthe?’ he said later. ‘Are you sure you wouldn’t rather be back sewing flowers onto wreaths?’

‘It’s not the sort of job you miss,’ I told him.

Paris 1917

She loves opening presents, getting her nail underneath the knot and easing it apart, unravelling it slowly, winding up the ribbon, finally . . . Snip. Marguerite leans over her and cuts the string. It falls away. Now nothing separates her from the contents but the flimsy paper wrapped around the package, but she doesn’t care what’s in the box now.

‘Happy birthday.’

Renée glances up and in the look that darts between them she feels Marguerite’s desire and knows whatever she has bought her is a token of it. It’s a signet ring. It isn’t flashy – a plain setting with a blue stone in the centre – imitation sapphire. But it’s not the sort of thing you’d pick up in the Marché aux Puces, which means that Marguerite has bought it from a jeweller’s. There is a label on the box that says as much.

‘It’s lovely,’ Renée says. ‘It must have cost an awful lot.’ The shrug that Marguerite gives isn’t quite as careless as it might be. Renée hesitates. The ring is slotted with the jewel facing upwards on a satin-covered base that momentarily reminds her of the pillow underneath her father’s head when he was lying in his coffin. She tries not to touch it when she takes the ring out. She rotates it underneath the lamp to catch the light, then slips it on the finger of her right hand. Marguerite gives her a quick glance.

‘Don’t you want to wear it on the other finger?’

Renée looks at her. ‘The middle finger, do you mean?’

‘I mean the finger on the other hand.’

‘But that would look as if I was engaged,’ says Renée.

‘It would look as if you were committed. After all, you are committed, aren’t you? We’ve been sharing this apartment for the past two years.’

‘Yes, but I don’t see why I have to wear it on that finger. Does it matter?’

‘If it doesn’t matter, why can’t you just put it on the finger it was meant for?’ Marguerite gets up and quietly clears the table.

Renée curls the twine around her index finger. There is not enough to be worth keeping but the ribbon circles it three times. She pulls it tight. Her finger reddens at the end and goes white at the base. She loosens it and blood flows back into the finger. Then she tightens it again. Her finger starts to throb. Her head begins to throb as well.

As they climb into bed that evening, Marguerite puts out her cheek and Renée plants the statutory kiss on it. They lie there rigidly, the space between them like a ditch they run the risk of falling into. They had hardly slept at all the night before. The sirens went off just before eleven. They’d unlatched the windows to avoid them blowing out and fifty minutes later they could hear air rushing back into the gas pipes; then the sirens suddenly went off again and people who had started coming from the cellars ran back down.

If there’s an air raid in the middle of the night, they don’t go down into the shelters. This is Marguerite’s decision. When the shells start falling, she turns over on her back and lies there with her body open and her arms outstretched as if she has a rendezvous with death and is accepting every invitation that she gets in case she doesn’t get another.

Renée rests her hand on Marguerite’s arm. She turns over slowly. Renée feels her breath against her face. It’s like the inside of a cupboard, dry and musty with a hint of lavender. She likes the fact that Marguerite’s lips aren’t wet like the swampy kisses she’s received from men who’ve kissed her in the past.

‘That’s better,’ Margo murmurs, pulling her into the narrow space between them. She wraps one arm round her shoulder. ‘I’ll look after you,’ she whispers. ‘You’ll be safe with me.’

Once, they had turned the bed into a bier and Marguerite had laid her out. ‘You’re not to move,’ she said. ‘Pretend you’re dead.’

When Renée’s younger sister Emilie had died, she’d helped her mother dress the body. Emilie had had her cheeks and lips rouged. She looked healthier than she had ever looked in life. The faint smile on her face was almost smug.

‘I’ll have to wash your body and then dress you in a shift,’ said Marguerite. ‘No matter what I do, you’re not to giggle. If you do, you’ll spoil it.’

Renée lay completely still while Marguerite undid the buttons on her blouse and drew her arms out of the sleeves. She disengaged the buckle on her belt and eased the skirt over her hips. Her hands moved up from Renée’s ankles and unlatched the garters on her stockings, rolling them back down towards her ankles and across the heel. She unlaced Renée’s corset, opening it up, and Renée, who’d been trying not to giggle, parted her lips silently to draw breat

h. Marguerite leaned forward suddenly and kissed her passionately on the lips. She looped her hands round Renée’s drawers and deftly drew them down over her thighs. As Renée lay pretending she was dead, it struck her that she’d never felt so much alive.

‘If you were ever to tell anybody – ANYBODY – what we did together, Renée, you would be shut out of Paradise for ever. Do you understand?’

Although she rarely questioned anything that Margo told her, Renée wondered how you could remain in Paradise no matter what you did, as long as no one knew about it. She felt vaguely that if she were to confess her sins, she wouldn’t be forgiven. Marguerite was right, perhaps. It wasn’t what you did that counted, but how well you kept the secret.

Bolivar got a direct hit in the night. The bomb fell on the Metro. People who’d gone down there to escape the raid were clambering over one another trying to get out again. She’s late for work, but Renée stops to buy a paper. On the placard it says sixty-seven people died. She thinks about the last one on the list and wonders if they’re male or female, if she’d ever passed them in the street, if they had ever come into the store and bought some perfume.

On the Place Saint-Augustin, the barrage of the night before has blown some of the shop signs off their hinges and the metal brackets hang above the street like gibbets. Renée sidesteps through the rubble, trying to avoid the clouds of dust and grit that puff into the air each time she puts her foot down.

She trips up as she’s about to cross the Boulevard Malesherbes. The strap has broken on her sandal; half of it is still inside the clasp. She only bought the shoes last week. She knew they wouldn’t last but she loves anything that glitters. She’s spent nine francs buying shoes that would have cost her five last year and which are useless anyway.

When she looks up, the man is staring at her from the pavement opposite. This is the second time this week she’s seen him. He’s dressed like an office worker in a black suit with a bowler hat, but there’s an unkempt look about him. He knows that she’s seen him, but he doesn’t move. She’s only two streets from the store. She keeps her head down, curling her toes up inside the shoe to give her foot some grip. Once through the glass doors, she runs up the staircase to the top floor, lifting her nose to catch the first dense whiff of jasmine and cologne that floats up from the counters to the lantern roof and, finding no escape, floats down again to meet her. Gabi is already there and so is Mademoiselle Lefèvre.

‘You’re late, Renée.’

‘Sorry, Mademoiselle Lefèvre. The roof collapsed over the Underground at Ménilmontant last night and I had to walk two stops.’

‘A new consignment came this morning. You can stay behind tonight and help me to unpack it.’

‘Miserable old trout,’ Gabi whispers. ‘After all, it’s not as if we’re being trampled underfoot by clients.’

Renée buttons up her uniform. She stops when she gets to the button at the neck, but then she does that up as well. She sees the man examining the rows of perfume bottles at the end of the display case. Gabi takes the roll of paper from the cash till and unwraps a new one. ‘Isn’t that the same man who was in here yesterday?’

‘He followed me into the store this morning.’ Renée sweeps her hair into the clasp behind her neck. She throws her head back and moves down the counter. ‘Can I help you, sir? Perhaps you’d like to buy some perfume?’ She’s already noticed that the suit is shiny at the elbows and the white cuffs underneath are darned. He’s not here to buy perfume.

He looks down the row of bottles and then glances back at her. ‘I’ve no idea which one to pick,’ he says. ‘You choose.’

She could just take the most expensive one and say, ‘That’s it’, but she goes through the rigmarole of taking out the stoppers, so that he can sniff them. He pretends he’s taking all this seriously, but by this time it’s a game that both of them are playing. Mademoiselle Lefèvre’s looking at them, so they have to keep it up. He smiles. He looks much younger when he smiles. He points to the bottle she’s picked up. She shakes her head. He moves his finger down the row and when he gets to freesia, she nods.

‘That’s settled then,’ he says, and takes his wallet out. He does have money after all, then. While he’s fumbling in his wallet, Renée takes a closer look at him. His hair is thick and still dark, but the beard has one or two grey streaks in it that have gone gingery around the mouth. He has nice eyes; eyes are important to her. It’s the round-rimmed spectacles that give his face that owlish look.

She crooks her arm and holds the bottle in the palm. The gesture is flirtatious but he doesn’t seem to notice. Mademoiselle Lefèvre, staring from the far end of the counter, knows exactly what is going on though.

‘Shall I wrap it for you?’

‘Yes, why don’t you?’

Renée takes a sheet of the exclusive wrapping paper that they keep for regulars. She ties the ribbon round the box and draws the blade along it so it curls up prettily. ‘There,’ she says, handing it across the counter. ‘I’m sure your wife will be pleased with that.’

He seems uncertain what to do with it now that he’s bought it. ‘Marthe doesn’t wear scent. She says animals tell friends from foes by smelling them and that’s the way we ought to do it.’

Renée thought the point of wearing perfume was to cover up your own scent. ‘So why did you buy it?’

‘It gave me an opportunity to speak to you.’

‘And now you have?’

He weighs the parcel in his hands. ‘Why don’t you keep the perfume?’

‘I’m afraid we don’t do refunds.’

‘Keep it for yourself, I meant. You chose it so it must be one you like.’

‘I work here. I’m paid to like all of them.’

‘Well,’ he shrugs. ‘Do you like this one or not?’

‘I like it.’

‘Take it then. Please.’

‘Don’t think I come with the perfume,’ she says, but she takes it nonetheless. It isn’t often that she gets to wear a scent that costs more than her wages for the week. Is he about to ask her out? She’d have to say no. She can’t go out with a man who can’t be bothered even to pretend he isn’t married. Anyway, he’s too old. ‘Was that all?’ She gives a brisk smile.

‘Do you work here every day?’

‘Except for Wednesday afternoons.’

‘Would you be free to take on something else on Wednesday afternoons?’

‘What did you have in mind?’

He rummages inside his pockets and takes out a notebook. There’s a card inside. ‘I wondered if you’d sit for me.’

‘Sit?’

‘Well, not sit exactly. Sometimes you’d be standing.’ He flicks through the notebook. ‘That’s the kind of thing I do.’ He hands it to her. There’s a drawing of a woman standing, one foot in the bathtub and the other on the mat, without a stitch on.

‘You want me to take my clothes off? Sorry.’ She moves down the counter. There’s another customer and Mademoiselle Lefèvre is beginning to make noises in her throat. She likes the girls to be polite to customers, but she’s decided this one is a waste of air and so has Renée.

She’s eighteen, although I don’t discover that till later. It’s the same age Pierre thought I was when we first met. Quarter of a century we’ve been together and he still thinks that I’m six years younger than I am. Too late to own up now. Most women only lie about their age when they’re ashamed of it. I always felt ashamed of mine – too young to matter or too old. As for Pierre, he settled on an age for me and I was trapped in it for ever. Have you seen those pictures of me in the bath? How old would you say I was there? It doesn’t matter what the date is; there I am, my hair still amber and my body like an hourglass, none of those ghastly blotches on my skin that later kept me in the bath all day. It was the perfect opportunity for him. I think he liked rooms that were small because they made him feel he wasn’t meant to be there.

He was a voyeur; no doubt about it. I’ve known plenty in my tim

e. There are the creepy ones who look at you as they would if they came across an animal run over in the road. If they discovered it was still alive, if they could see its heart was beating, they’d move on; real life is a distraction. Then there are the others – and he’s one of them – who don’t know what they’re looking for until they find it. When they do, they never let it go.

I used to think I’d know the kind of woman he would be attracted by. I thought it would be somebody like me – dark, melancholy, antisocial. Was I always like that, or is that what happens when you’ve spent the best years of your life with somebody who sees you as a splash of orange in the background of a still life? At least up till now I haven’t had to share the space with anybody else.

It’s Marguerite’s insistence that they have no secrets from each other that makes Renée want to keep things from her. ‘We must tell each other everything,’ says Marguerite, but Renée is already thinking, ‘What if I don’t tell her everything?’ or, ‘What if what I tell her isn’t true?’

She always knew when she’d attracted somebody’s attention. Normally it was her hair they noticed first. It was so pale that people often thought she’d bleached it. It was not just men – she often noticed women sneaking glances at her, too.

The stare she got from Marguerite when they got on the same bus in the mornings wasn’t like the stares she got from women normally, the sort of stare that wanted what she’d got. This was a stare that wanted what she was. One morning when she had been hanging from the strap at one end of the tram and Marguerite was seated some way down the bus and facing her, she’d let herself swing slightly on the strap so that her eyes fell naturally on Marguerite’s. She had expected Marguerite to meet the gaze or look away, but what she did was raise her eyes a fraction so that she seemed to be looking not at Renée but beyond her to a place of infinitely greater promise.

Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies