- Home

- Lynn Bushell

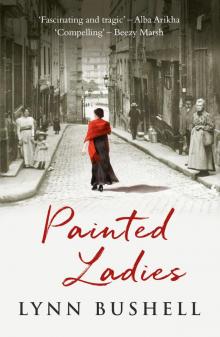

Painted Ladies Page 4

Painted Ladies Read online

Page 4

‘Marguerite . . .’

‘What?’

Renée shrugs. She’s toying with the ring. She takes it off again and tries it on another finger. Then she tries it on the other hand. She holds the finger out. ‘It’s quite a nice ring.’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘I think I’ll leave it on.’

He sighs. ‘Good, that’s decided then.’

They work on late into the afternoon and go down to the café when the session’s over. La Rotonde is where the painters meet to talk and drink and it is always full of artists arguing and shouting. As they go in through the swing doors, Renée gets a whiff of freshly ground and roasted coffee beans, a scent you hardly ever come across outside the cafés any more. She’s noticed that a lot of things that are in short supply – eggs, coffee, cigarettes – seem to be plentiful enough if you know where to go for them.

Pierre steers her deliberately to a corner of the room that’s empty. Renée loves the noise and bustle of the café, but for Pierre it’s a distraction. She doubts that he ever goes there when he’s by himself.

‘Why do the painters all live in this part of town?’

‘It’s cheap and painters like to live on top of one another. Some do, anyway.’

She picks up snatches of the conversation on the table next to theirs. ‘What are they arguing about?’

He takes out his tobacco pouch. ‘A Polish countess has been commandeering vans to transport soldiers to and from the front.’

‘Is that a good thing?’

‘If she wasn’t Polish and a countess and if they were not the vans used by couturiers and if the chauffeurs weren’t in uniforms that she’d designed herself, nobody would have given it a second thought.’

‘I don’t see . . .’

‘Nor do I,’ says Pierre. ‘They say she’s doing it to advertise herself.’

‘Who is she?’

‘I believe her name is Misia Sert. Jean Cocteau is a friend of hers. The two of them were photographed together in Le Figaro.’

Occasionally, Margo brings home copies of Le Figaro or, if she finds one on the Metro, Renée picks it up, but normally she skips the news. She hasn’t heard of either of them.

‘So, are you on her side?’ she says.

Pierre cups a hand over the pipe. ‘I’m not on anybody’s side. I just wish that the war was over.’

The noise ratchets up. One man lets out a swear word in a language Renée doesn’t recognise although she gets the gist of it. The man is short and swarthy, and the energy is pumping out of him in waves. He throws his arms out to embrace the room but always ends up pointing back towards himself as if he’s trying to corral a swarm of feathers that have just erupted from a bolster.

‘That’s Picasso.’ Pierre looks away. ‘He’s recently been taken up by an American called Gertrude Stein. She picks up artists with a small amount of talent and recycles them as geniuses.’

Renée doesn’t understand what half of them are saying but it sounds exciting, dangerous. She wishes she was sitting at their table.

‘Is he someone I should know about?’

‘I doubt you’ll hear much of him in the future, but he’s talked about a lot now.’

‘Does he paint like you?’

Pierre turns so that he is not in anybody’s line of sight. ‘Picasso? No. He hates my work.’

‘Do you hate his?’

‘Let’s just say that we differ in our attitude to art.’

‘Why do you have to have an attitude? Why can’t you just paint?’

‘You don’t have much choice about the way you paint, that’s true.’

She lets the noise wash over her. She’s not the only woman there, but none of them are making any contribution to the conversation. One man keeps on casting glances at her. Renée recognises him. This is the man she walked past in the street outside the studio. The same girl’s sitting next to him. She’s making small dips with a spoon into a water ice, then raising it with little darting movements to her lips.

‘Who’s that man in the white suit?’

Although Pierre has got his back to him, he knows who she’s referring to. ‘Roussel.’

‘Why is he staring at us?’

‘I imagine you’re the one he’s looking at.’

Since she’s been coming to the studio, she has got used to being looked at in a certain way, but Roussel’s look is like the ones you get from navvies when you pass them in the street.

‘Try not to stare back quite so obviously,’ Pierre says. ‘I would rather that he didn’t come across.’ But it’s too late. Roussel is on his feet already.

‘Mind if I sit down?’ He pulls a chair out without waiting for an answer. ‘My name’s Ker-Roussel. And you are . . . ?’

Renée glances at Pierre. He hasn’t yet acknowledged Roussel. ‘Renée Montchaty.’ She notices how finely tailored Roussel’s shirt is and how well it fits him. When he speaks to Pierre, he keeps his eyes on her. They are the coldest blue she’s ever seen. ‘We haven’t seen you in here for a while, Pierre. You’ve turned into a hermit.’

‘I’ve been working in the studio.’

‘You must have come out of the studio at some point to have lit on this delightful creature.’

Pierre adjusts his spectacles. ‘She came to me.’

Not quite true. Doesn’t that make her sound rather forward, Renée thinks.

‘You don’t say? Well, I wish she’d come to me instead.’ Roussel laughs. ‘How is Marthe?’ He is making sure she knows Pierre is spoken for.

‘She’s well. It’s kind of you to ask.’

‘You still spend time in Saint-Germain-en-Laye?’

‘Of course. It’s where I live.’ He looks at Roussel. ‘And your family? How’s Isabelle? And what about the girls?’

‘They’re fine.’

‘Annette must be . . . what, fifteen?’

‘Fourteen,’ Roussel says abruptly.

They are interrupted by the low wail of the siren and a groan goes up from the adjoining tables.

‘Do you want to go down to the shelter?’ Pierre says. No one else is moving.

Renée shakes her head. There’s an explosion nearby. Glasses on the table rattle. In the first months of the war, Parisians came out onto the streets to watch the Taubes circling. People joked that you were more at risk from shells fired by your own side than you were from bombs dropped by the Germans. It’s not like that now. The streets are clear within a minute of the sirens going off.

The girl on Roussel’s table goes on spooning water ice into her mouth. Her face is pretty but her body has an undev-eloped look about it. There’s a small dog sitting at her feet. She pats it absently and dips her finger in the ice so that the dog can lick it. They wait till the noise of the bombardment has receded.

Roussel lights a cigarette. He looks at Renée as he throws the match away. ‘What did you do before Pierre discovered you?’

She hesitates. She doesn’t want to own up that she is a shop girl.

‘She lived with her family in Bobigny.’ Pierre gives a complicit smile. She’s flattered suddenly to find herself the centre of attention, though she is embarrassed for the girl on Roussel’s table who, now that the ice cream has all gone, is staring at them.

‘Do you work for Pierre every day?’

‘Not every day.’

‘What days would you be free to work for someone else?’

Pierre is toying with a card of matches he has taken from the ashtray.

‘I’m not free on any of the other days,’ she says.

‘You lead a busy life.’

‘She has commitments,’ Pierre says, quietly.

Roussel looks from Pierre to her and back again. ‘I take it those commitments are exclusively to you.’

‘Yes,’ Pierre says evenly. ‘They are.’ There’s silence round the table. Renée blushes. What Pierre is saying is that she’s not just his model. She can’t contradict him without giving Roussel the impression

that she is available for anyone who cares to make an offer for her. She feels angry but she’s not sure who she’s angry with or why.

Roussel feels in his pocket. ‘Take my card in case you change your mind. I’m always looking for a new girl.’

‘Looking for a new girl’ almost makes it sound as if he’d pick one off the street. Her eyes pass to the girl on Roussel’s table.

‘Caro works for several of us,’ Roussel says. ‘You earn more that way.’

Renée reaches for the card, then wonders if she should have left it on the table.

Pierre takes out a note and tucks it underneath the saucer. ‘You’ll forgive us if we leave you, Roussel; we still have some work to do.’

Roussel looks keenly at her. As he’s gone on talking she’s been looking at the sagging skin around his jaw, the drinker’s raw cheeks. He is still a handsome man, but there is probably no more than three years difference between him and Pierre.

The girl on Roussel’s table runs her finger round the inside of the ice cream bowl and puts it to her mouth.

‘Is he someone you’ve known a long time?’

Pierre stops to button up his topcoat. It’s cold outside on the pavement. ‘We were students at the Beaux-Arts in the same year, although I was two years older; I’d already done my law degree.’

‘The two of you were friends, then?’

‘Not exactly. We were in the same place at the same time, that’s all.’

It’s begun to rain. She takes his arm; the pavement’s narrow. ‘Don’t you like him?’

‘I’m not keen on him.’

‘You didn’t have to make it look as if I were your mis-tress.’

‘I said nothing of the kind,’ he mutters. They walk on a few yards without speaking.

‘That’s what everybody thought.’

‘If you knew Roussel better, you would know that it’s the way he thinks.’

‘So I’m no better than a street girl?’

‘I believe I’ve always treated you with the respect that’s due to you.’

Is this the problem? Renée wonders. ‘Are you angry at me?’

He looks calmly at her. ‘Why would I be angry?’

‘You thought I was flirting with Roussel.’

‘And were you?’

She stares back at him. ‘Well, so what if I was? It’s not as if you own me.’

‘Quite.’

‘I wasn’t flirting with him anyway. I didn’t even like him if you must know.’

‘As you’ve been at pains to point out, Renée, I don’t own you and of course you’re free to work as Roussel’s model if you want.’

‘I don’t . . .’

He puts a hand up. ‘And you’re equally free not to. When you came here it was understood that our relationship would be professional.’

‘I still thought we were friends.’

‘We are friends and because we’re friends I would advise you to keep Roussel at a distance. Everything he does, he does for selfish reasons. I would hate to see your life spoilt. Can we move on?’

She walks sulkily beside him. She’s not certain what she wants from him, but if she’s going to continue to risk Marguerite discovering what she’s been doing, she wants more than this. There was a moment in the café when she knew Pierre was jealous. Most men when they’re jealous fight for what they want. He goes the other way. He’s like a snail retreating back into its shell. Once there, it doesn’t matter how long you stand over it, it won’t come out again. She has an urge to shake him sometimes to wrest some kind – any kind – of a response from him.

They’ve reached the entrance to the studio, but Pierre keeps on walking. Renée runs to catch him up. ‘Where are you going?’

‘To the tram stop.’

‘Don’t you want to go on with the painting?’

‘Not today. I don’t feel in the mood.’

‘Is that my fault?’ She doesn’t want the afternoon to end like this.

‘Of course it’s not. It’s just that once I’ve stopped, it’s harder to get started.’

‘You told Roussel that’s why we were leaving.’

‘I preferred to spare his feelings. I could just have said I didn’t care to spend another minute in his company.’ He slides one hand under her elbow and propels her through the traffic to the stop. They wait in silence. When the tram comes, he stands back to let her on. She waits for him to kiss her, but he doesn’t.

For months after that day, I dreamt I was floating in a lake just underneath the water with a film of thin ice over me. I couldn’t breathe but in the dream I didn’t need to; I was dead already. I think maybe for a short time, seconds possibly, I did die that day in the bath. My body never seemed to be entirely mine from then on. I would wake up in the mornings with odd welts and rashes on my arms and legs as if something had got in underneath my skin and couldn’t find its way out.

Pierre was careful after that. Once we had got a proper bath, he made sure that the water never fell below a certain temperature and that I had breaks every hour. I was worried that he wouldn’t want to paint me with the rashes on my skin but they were a reminder, I suppose, of that day when he nearly lost me. It became a bond between us.

There was no one else. He never introduced me to his family, even Andrée. When we first began to live together, I was glad I didn’t have to meet them and then I began to wonder whether it was them or me he was ashamed of. Since I couldn’t take him home to meet my family, I could hardly make a fuss about not meeting his.

He never knew about Suzanne. I wrote to her after she died. I tore the paper into little scraps and threw them from the window of the studio. They floated down into the street and gusted into doorways and shop windows, like confetti. Bits of them clung onto people’s jackets and were carried home with them. It was my way of letting the world know she’d been here.

Pierre came up behind me and looked out over my shoulder. ‘Look at all those bits of paper,’ he said. ‘I expect there’s been a wedding in the church.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I expect there has.’ Why couldn’t I have said it was a requiem for our lost child? Perhaps because if he had known, he would have grieved. He would have looked to me for comfort and I couldn’t give him any. I had none to spare.

There isn’t anybody now, except Suzanne. She keeps me company. But I don’t want to burden her with this. The dead have some rights. What’s the point of being dead if you have to put up with everything you’d be expected to put up with if you were alive?

Last night when I looked in the mirror, I found two grey hairs both growing on the same side of my fringe. And now I see the rash beginning to appear again. It started in the little creases in my elbows and behind my ears – a faint bloom that gives colour to the grey skin round it. Now it’s spread across my neck and upper arms. I shouldn’t scratch it, but I do. The only thing that eases it is water.

B

When she turns up at the studio the next week, Renée finds it locked. Pierre would normally be there before eight-thirty. His routine is stricter than an office worker’s. She does not want to run into any of the other painters in the block, so she goes down and walks the streets for half an hour before coming back. The door is still locked.

She is angry that she’s wasted not only the fare to get there but an afternoon when she might have been doing something else. That Pierre should finish with her like this goes against what Marguerite has told her about men and how they normally conduct themselves. When Marguerite was in her early twenties she had an affair with somebody she knew at work. ‘That bastard had the best years of my life,’ she used to say, ‘and I got damn all in return. Let me be an example to you, Renée. Men are only interested in one thing.’ But in that case, why would they give up before they’ve got it? Pierre’s kept Marthe on for quarter of a century. But then, as he was only too quick to remind her, Marthe is his muse.

That they should quarrel over someone like Roussel seems unbelievable. She tells herse

lf she wasn’t flirting with him, but she can remember that sharp slither of excitement when she knew that finally she had got somebody’s attention, and not just Roussel’s.

‘You’re miles away. What is it?’

Renée looks down at the magazine, but Margo goes on staring at her and the colour starts to rise in Renée’s cheeks.

‘You’ve been behaving oddly all week. Is there something that you haven’t told me?’

‘No.’

‘You haven’t been laid off from work?’

She realises it’s the perfume counter Marguerite’s referring to. ‘Of course not. Why would I be laid off?’

‘I thought something must have happened at the store.’ She waits while Renée goes through the pretence of thinking.

‘Did you go and see your mother this week?’

Renée shakes her head.

‘It must be three weeks since you paid your family a visit.’

‘I don’t think it’s that long.’

‘How long is it, then?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘Won’t she think it strange, her being ill and you not bothering to visit her?’

‘It isn’t that I can’t be bothered.’

‘We could go down this weekend together, if you like.’

The pause that follows is a fraction too long. ‘Not this Saturday. The store is going on the outing to the Bercy funfair.’

Margo looks at her. ‘You never said.’

‘I thought I had. It’s always the first Saturday in April.’

‘Just because it’s always then, it doesn’t mean it always will be. There’s no reason why I would remember, anyway.’ She taps her pen against the form she’s filling in. ‘You’re going, then?’

‘It’s only once a year. You don’t mind, do you?’

‘Not at all. The weekends are the only time we have together, but of course if you would rather see your friends . . .’

‘It’s not . . .’

‘I’ve said go.’ Marguerite writes for a moment and then puts the top back on her pen. ‘I’d thought of doing something else in any case, this weekend. There’s a concert at the Châtelet. The head clerk at the Mairie invited me. It’s Saint-Saëns.’ She smiles cynically. ‘Too serious for your taste.’

Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies